LITTLE ENCYCLOPAEDIA

SCRIPTURES

The scriptures – Shruti

The Shruti is Divine revelation. From the Sanskrit root shru, “to hear”, it indicates the Knowledge perceived by the wise seers, rishi. It contains universal values that are valid forever. The Vedas and the Upanishads are considered Shruti. Some traditions, however, include other texts too. The Smriti is based on the authority of the Shruti, but it was compiled by man. It adapts the eternal values of the Vedas to the historical contingency by determining the social, family and individual norms and observances of each Hindu. Among the texts of the Smriti, there are the doctrinal treatises on the trivarga (dharma, artha, kama), in particular the normative ones, Dharma-shastra and Smriti; the Itihasas, Puranas and Nibandhas.

The Veda

The Veda is sacred Knowledge, the divine Truth. There has been no human operation, apaurusheya, and it is eternal, anadi. The Veda outlines the boundaries of Hindu orthodoxy: it is the supreme authority, Praman. It contains the foundations of Hindu culture, spirituality, arts and sciences. The compilation of the Veda has been attributed to the rishi Vyasa. He transmitted it orally to his four disciples who gathered it in large collections, samhita: the Rig-, the Yajur-, the Sama- and the Atharva-veda.

The various spiritual traditions, sampradaya, rose from these rishis. The Vedas have been preserved intact over time thanks to the extraordinary mnemonic capacity of the priests, brahmins, in charge of transmitting them and safekeeping their knowledge. Significant is the image of the Veda as a large body, Veda-purusha, of which each member is made up of a specific Scripture. In addition to the four collections, the Veda includes a series of ritualistic manuals, Brahmana; supplementary works, Aranyaka; speculative and exoteric texts, Upanishad; groups of auxiliary texts, Vedanga. From the Vedangas, elaborated to decode the teachings of the Veda, authentic sciences arise such as phonetics, siksa; grammar, vyakarana; meter, chandas; etymology, nirukta; astrology, jyotisha; ritual practice, kalpa. The Vedangas, written in the form of aphorisms, are known as Sutras. The Veda contains more than one hundred thousand verses, of refined poetry and mysticism. In the Veda, we can see the awareness of the unity and interdependence that bind living beings, the cosmos and God.

Vedic theology portrays a vision of the Universe governed by an unfailing order, rta, on which both the macrocosm and human, ethical and social conduct are based. This order is maintained, according to Vedic religiosity, on the ritual sacrifice, yajna, addressed to the deities invoked in the hymns. The Vedic pantheon counts 33 million gods. This number is only symbolic and expresses the infinite functions of one absolute God without a second. In this regard, the Shankaracarya of Kanchi, Sri Chandrasekharendra Sarasvati states: “The Vedas reveal to us the Truth of the One in the form of many Deities. The worship of each of these is like a ghat on the river called the Veda. […] These different forms are like branches that have the same roots”.

Read more . . .

Upanishad

The Upanishads are also known as Vedanta, “the final part of the Veda” or “the scope, the quintessence of the Veda”. The major ones are 108. They are in the form of dialogue between Guru and disciple. The Upaniṣads have references to the ritual but prefer a speculative approach. They explore the deep quests of existence: the nature of God, of man, death, the purpose of life and spiritual fulfilment. They summarise the outlines of the concept of Brahman, the Absolute, of Atman, the Self; of the doctrine of karman; the subtle physiology of yoga, and many others. Knowledge, jnana, becomes the preferred means to experience the identity between the individual self and the universal Self, Atman-Brahman.

Upaveda

The Upaveda, “minor Vedas”, derive from a Veda. Considered in between Shruti and Smriti, they contain important disciplines such as medicine, the arts, good governance and the science of weapons.

Ayurveda is the science of life. It is among the oldest traditional systems of healthcare. It has a holistic approach to disease and is closely linked to the evolutionary path of man. Ayurveda is a Sanskrit term composed of AYUS = LIFE or LONGEVITY and VEDA = KNOWLEDGE; it is therefore a science that considers life in its totality. Ayurveda is based on the observation of living beings, in their wholeness of body, mind, soul and indriya (senses), as well as everything around them: food, emotions, lifestyle, language, climate, flora and fauna. References to Ayurveda are found above all in the Atharva-Veda.

The history of Ayurvedic clinics and universities dates back 3000 years. It is a medicine widely used in the East and, today, widespread all over the world. Initially, Ayurveda included 8 disciplines: Kaya Chikitsa, Bala Chikitsa, Bhuta Vidya, Urdhvanga Chikitsa, Shalya, Danshatra, Jara, and Vrista Chikitsa. Later, other branches developed. In ancient times, surgery was very advanced. Ayurveda, as the other Indian sciences, has a divine origin; it was brought to men by Dhanvantari who emerged from the blending of the ocean with the collected amrita, the divine nectar that conferred immortality. Dhanvantari is also considered to be the father of surgery. His disciple Susruta, wrote a classic treatise on plastic surgery; the rhinoplasty techniques described by Susruta are still followed today by surgeons.

Dhanurveda

It is the science of the use of weapons, from dhanur which means “bow”. Based on a strong moral and ethical sense, Dhanurveda tackles the problem of defence and war with a scientific approach and rigour. It describes in detail the ethical code that the warriors had to observe, the different types of weapons, the training of the army, the care of animals – especially horses and elephants – used in battle. The texts are divided into four sections: initiation of the student, role of the student, mastery in the art of weapons and their use.

Weapons are divided into shastra and astra; the former are effective for their intrinsic power and the ability required to use them, the latter for the power evoked by the mantra. The warriors were subjected to severe discipline and precise rules including the absolute prohibition of injuring civilians or enemies who had surrendered; the battle had to be limited to the war field; a warrior could not be attacked during preparation to the battle or if unarmed; the enemy camp had to be respected at night and the fighting resumed only at dawn. The use of weapons was strictly limited to the defence of the weak, of ascetics who carried out meditative practices, of holy men, beggars, women and children.

In a culture in which the supreme good, paramo-dharma, is non-violence, ahimsa, war was the last alternative to preserve dharma, justice. A complex and still current issue is that of reconciling non-violence and the need to defend the principles of good even with war. This is part of the vision of the manifestation based on opposites that do not in fact have a negative value; in Vedic society no value was set as absolute, since everything in the manifestation is relative.

According to tradition, the 6000 verses of the Dhanurveda were handed down from Shiva to Parashurama and from the latter the tradition (paramparaya) continued with Vasishtha, Vishvamitra, Drona, Bhoja and many more. Dhanurveda is mainly based on Yajur-veda and was addressed to the warrior class, kshatriya, whose primary purpose was to defend people and dharma.

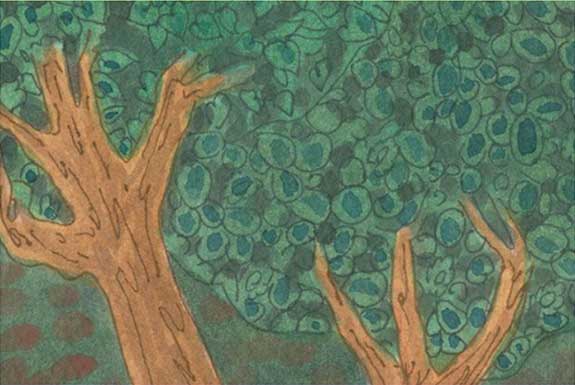

Gandharvaveda

It is the science of music and dance. The recitation of the Veda, particularly of Sama-veda, gives great importance to notation, to sound, with emphasis on singing. We find references to a rich variety of instruments in ancient India: percussion, wind instruments, strings, many of which are still used today.

This has its echo in a refined theology and science of sound that has few equals in the world. Manifestation is pure vibration; sound is creative power; the knowledge of mantra and music becomes a means to rediscover this original reality. “He who knows the shades of the sound of the lute, thanks to the knowledge of the shruti and the combination of the scales of the notes, and has the understanding of what is real, effortlessly reaches the ultimate goal, moksha.”

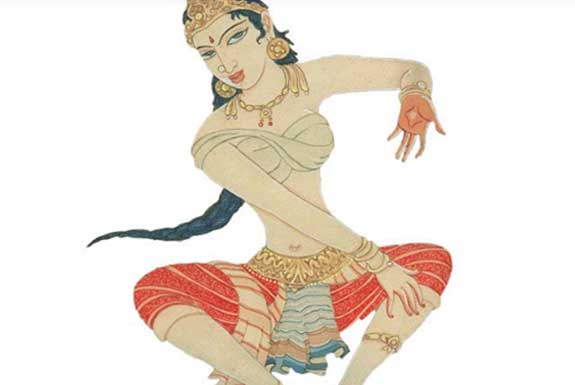

The interrelation between all the beings of creation is the same that exists between musical notes; the manifestation is an extraordinary melody, raga, in which the notes, composing themselves, delight the mind. Gandharvaveda offers a global vision of the arts that inspires and educates artists to an intimate experience to achieve their essential nature. The artistic expression in which the principles of Indian aesthetics are achieved is of great importance. Art means interpreting bhava, feeling and emotion, and the completion of this expression is rasa. Rasa is the aesthetic experience, it is the quality of communication between the artist and the viewer, it is the beauty of the art presented by the artist that offers an extraordinary key to the understanding of human emotions. The concepts of “emotion” and “feeling” in the aesthetic experience recur significantly in a term that calls one of the six classical dances of India, the Bharata Natyam. Natyam indicates the theatrical performance, and Bharata does not seem to refer simply to the sage Bharata, who codified the quintessential treatise on dance and music, the Natyashastra. The semantic meaning of the term emerges

The semantic meaning of the term emerges from the subdivision of the word into ba = bhava ra = raga ta = tala, therefore “representation of feelings through a melodic structure on a rhythmic basis”. In dance, the different roles of the artist characterize emotions, bhava, and moods. As in reality, according to situations, different roles are assumed: a person, for example, can be father-mother, brother-sister, son-daughter, husband-wife, so the artist interprets life. In life, the Self is distinct from roles, just like the artist from the characters he plays.

Similarly, something sublime happens in art, bhava evokes a rasa. The artist can help in understanding the “play of life”, helping to avoid identification with roles, but reminding that the true self is a witness. It is so for the mystics and sages who have experienced the immutable Self and who experience creation in full freedom and harmony; their lives are the play of the Lord and their emotions, bhava, embellish their lives like rasa. The same meaning of aesthetic representation is found in music, in the infinite combination of notes that represent the elements of nature, which enclose the supreme mystery of creation in its most subtle form: the vibratory form of sound.

Artha-shastra

It is a treatise on politics, state administration, commerce. Among the fundamental purposes of life, purushartha, artha is the material and spiritual well-being of all creatures who live in harmony with dharma. The final treatise on Artha-shastra is attributed to Kautilya, advisor of the great Emperor Candragupta, and dates to 4th century B.C. The origin of the Artha-shastra is mentioned in the Shanti-parvan of the Mahābhārata. It is said that Lord Brahma handed down this knowledge to ensure harmony and peace in society. The work originally consisted of one hundred thousand chapters relating to dharma, kama and artha. However, as man’s life became shorter and shorter, with the decay of the eras, yuga, Shiva simplified the text by reducing it to ten thousand chapters.

The Scriptures – Smriti

Sutra

Kalpasutra

Based on tradition, shruti, these texts give instructions for the celebration of solemn rituals, yajna. They derive from a re-elaborated version of the Brahmana. Over the centuries, they acquire an increasingly obscure character.

Shulvasutra

Supplement to the Kalpasutra. They are a valuable source of knowledge of Vedic mathematics. Specifically, they deal with measurement (shulva means “rope”) and the construction of altars, see, for the ritual of fire. Smartasutra: all the texts that are based on the smriti, or on what in the tradition is not explicitly expressed; they generally deal with family and domestic rituals and social duties.

Grihyasutra

Texts governing rituals, samskaras, and other ceremonies, celebrated by householders, explaining the procedure, the sutramantra used and the social aspect. Dharmasutra: texts (directly related to Grihyasutra) in which social duties are specified in reference to one’s social status.

Shastra, doctrinal texts

The doctrinal texts, shastra, have as their object the three purposes of human life, trivarga, (dharma, artha and kama). Those related specifically to dharma are known as Dharma-shastra. The Dharmashastra can be considered the civil and penal code of ancient India. Some texts are still taken into consideration today by the Indian High Court, in certain cases relating to Hindus. They include, in fact, the laws relating to religious, moral and social duties. This group of texts, also known as smriti, are ascribed to 18 rishis: Manu, Yajnavalkya, Parashara, Gautama, Harita, Yama, Vishnu, Shankha, Likhita, Brihaspati, Daksha, Angiras, Pracetas, Samvarta, Acanas, Atri, Apastamba, Satapata.

These sages probably drew these indications directly from the Vedas and transcribed in texts such as the Manu-smriti, the Yajnavalkya-smriti, explaining what is lawful to know in relation to dharma, rituals and sacraments that men and women must respect during their life. The texts related to artha, on the other hand, are about good governance, politics. The most famous is the Artha-shastra, attributed to Kautiliya or Canakya. It is a compendium on politics, administration and economy. Vatsyayana’s Kama-sutra on the art of love is well known. It also deals with the 64 arts: dance, singing, painting, and so on.

Itihasa, “So indeed it was”, ancient teachings

The Itihasas form the Hindu epic. Composed not only in Sanskrit but in vernacular languages too, they express the complex teachings of the Vedas and Upanishads in the form of tales and myths, thus making them accessible to all members of society. They are centered on human and divine figures, ideal models for realizing the four purposes of life, purushartha: dharma, artha, kama and moksha. The two main Itihasas are: the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.

The Mahabharata

The Mahabharata by Vyasa is a great epic that describes the war between two families, the Kauravas and the Pandavas, in which Prince Krishna takes part favouring the Pandava army. There is no theme of religion, philosophy, religion, mysticism that is not considered in this great epic. It contains the highest and noblest moral principles, useful lessons of all kinds, countless stories, episodes, parables and dialogues that reinforce moral and metaphysical principles. The Mahabharata includes the Bhagavad Gita, the dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna, one of the Pandava princes, which takes place on the battlefield before the final confrontation between the two armies. The universally known poem, which presents Krishna as a divine figure, is rich in ethical teachings and is a guide on the different paths (marga) of yoga. An appendix to the poem is the Harivamsa, “The lineage of Hari”.

The Ramayana

The first epic poem by the sage Valmiki that tells the story of the king of the Solar Dynasty, Rama or Ramacandra, of his birth, education and marriage, his exile during which his wife Sita was kidnapped by the demon Ravana, King of Sri Lanka, finally defeated, and Sita released.

Through the events and the ideal personality of the characters, Rama and Sita, the ethical principles of dharma are explained clearly to all and models of behaviour are given, examples of noble human qualities such as courage and loyalty; the poem gives a living image of life at the peak of the Vedic civilization.

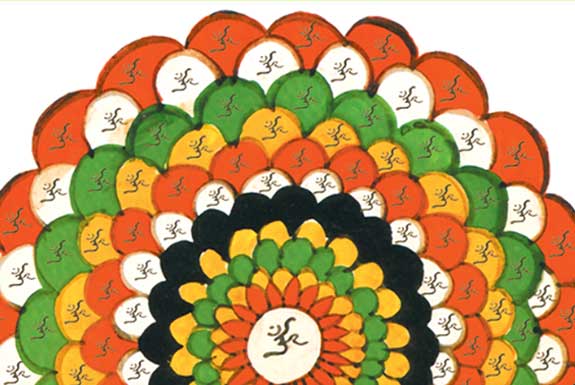

The Purana

“Purana” means “ancient”, not only in the historical sense of the term but in the ontological sense too. Brahman, the Absolute, is ancient par excellence; it is the ancient truth of the Vedas handed down orally from mouth to ear.

The Puranas are guardians and spokesman of this Vedic knowledge, but they adapt it in a simplified form.

Like the Itihasas, the Puranas are also addressed to everyone, not only to priests or scholars. Handed down by a category of cantors or bards, the suta, the Puranas have an encyclopedic nature. They contain uplifting tales, references to worship, mythology, iconography of the main deities of classical Hinduism, celebrations, mahatmyas, sacred places, tirthas, deities and holy figures. There is a lot of emphasis on devotion, bhakti, pilgrimage, yatra, vows, vrata, and the practice of charity, dana.

It is believed that originally there was only one great Purana, enormous and eternal. This Purana would later be reduced to 400,000 stanzas divided into 18 major parts, Maha-purana, to which 18 minor parts, Upa-purana, were added. The Puranas are usually divided according to the dominant quality (guna), sattva, rajas, tamas, and therefore associated respectively with Vishnu, in the function of preserver, with Brahma in the function of creator, and with Shiva in that of transformer. Traditionally the Puranas have 5 characteristics, pancalakshanas. However, this is more artificial than real, in fact, these five themes are not present in many Puranic texts.

The pancalakshana are:

1) creation of the universe, sarga

2) cyclic nature of the cosmos, pratisarga

3) the genealogy of the Gods, vamsha

4) cosmic eras, manvantara

5) story of the great dynasties: solar and lunar, vamshanucharita

Kavya, art literature

Kavya can be defined as art literature, Indian refined poetry. It is distinguished, in fact, by a refined use of tropes, alamkara, and is based on an elaborate science of sound which is entrusted with the task of conveying meaning. The words are carefully chosen to produce an inseparable relationship between sound, shadba and meaning, artha.

The main purpose of Kavya is to inspire rasa: the feeling, the aesthetic experience, comparable to the mystical one. Other commentators (Anandavardhana 9th century) preferred the expression “fascination”, dhvani.

Kavya can be studied based on its:

• fruition – it can be shravya, heard, therefore intended for reading or it can be drishtva, seen, through dramatic representation

• composition – it can be in verses, padya; in prose, gadya; a combination of verses and prose, Mishra

• extent – it can be short, laghukavya; long, mahakavya

The main topic of Kavya is love in union, sambhoga, or separation, vipralambha.

Kalidasa, one of the “nine jewels” at the court of King Gupta Candragupta II, is among the greatest exponents of Kavya.

Second period of the Sutra or of the Darshana (philosophical literature)

Texts written by the founders of the different schools of philosophical thought through which the currents of thought were rearranged in a more systematic and concise way (in the form of a sutra in fact).

The points of view or darshana and the related texts are:

– Purva mimamsa / Mimamsa-sutra by Jaimini

– Uttara mimamsa / Brahama-sutra or Vedanta-sutra by Badarayana

– Samkhya / Samkhya-karika by Kapila

– Yoga / Yoga-sutra by Patanjali

– Nyaya / Nyaya-sutra by Gautama Aksapada

– Vaisheshika / Vaisheshika-sutra by Kanada.

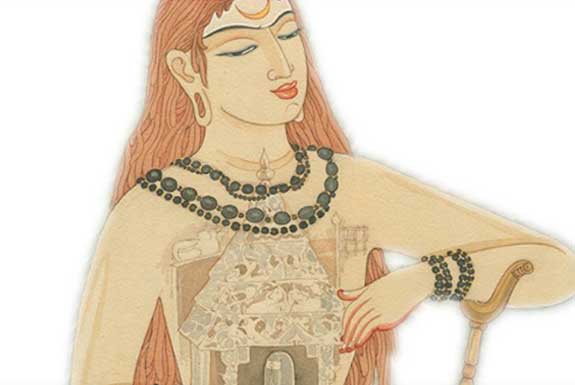

Tantra “structure, system, doctrinal treatise”

The generic definition of “tantra” includes an enormous number of texts of both a religious and secular nature. “Tantra” comes from the Sanskrit root “tan” which means “to stretch, to weave”, and “structure, system”, “doctrinal treatise” too. This term also refers to texts from the Jain and Buddhist traditions. Generally, it indicates the texts of the Shakta doctrine, as well as the literature in which the religious life and the various Hindu traditions, sampradaya, are kept.

Tantra includes Hatha-yoga texts, treatises relating to cult, the worship of mystical diagrams and so on. The Tantric texts claim the character of orthodoxy: in fact, they call themselves shruti and agama (sacred tradition handed down), and they define themselves as the fifth Veda.

Tantrism has a decisive role when man is unable to understand the truths contained in the Upanishads. It offers individuals of the present era, kali-yuga, the possibility of liberation from the cycle of rebirths, through an evolutionary system containing the essence of the Vedic sacrificial cult, of the upanishadic monism, of the bhakti expressed in the Puranas, of the yoga expounded by Patanjali, and the mantric elements of the Atharva-Veda.

Traditionally, Tantras are composed of some doctrinal parts, others dedicated to rituals, worship and spiritual techniques. They include the Agamas.

Agama

Agama means “that which has been handed down” and refers to an ancient tradition regarding the veneration of the divinity and the philosophical, psychological and ritualistic aspects revealed orally and through written texts.

It is the revelation of a traditional knowledge (agama), that is, that which comes out of Shiva’s mouth and enters Parvati’s ear. When, on the other hand, it is Parvati who reveals knowledge to Shiva, it is called nigama. The Agamas are mainly traced back to the Shaiva and Shakta sources, but those alongside the pancaratra are also attributed to the Vaishnava sources.

The Pancaratrika Vidhi, that is the combination of the Vedic and Tantric ritualistic systems, is at the base of the Vaisnava Tantra. Traditionally, 64 texts are listed, classified according to the Divinity adored.

Shaiva: 28 classical Agama

Vaishnava: Pancaratra, Vaikhanasa

Shakta or Tantra: Mahanirvana, Kularnava, Pancasara, Tantraraja, Rudrayamala, Brahmayamala, Visnayamala, Todala.