YOGA

YOGA: A LONGING FOR UNITY

Thousands of visual, auditive, touch, taste stimuli; human and mechanical crowds, high speed electromagnetic waves; the worries of life caught in a whirlwind of senses, of confused desires; a frantic pressing forward towards phantasmagorical goals.

This is the partial image offered by the kaleidoscope of today’s society. And yet, if on the one hand, we witness the fall of values and of community cohesion, on the other, we hear an even louder cry in search of meaning, unity and freedom.

A yearning for unity so innate in the culture of India to be remembered and emphasized daily in the common greeting gesture, namaste, in which both hands are joined in front of the heart. Symbolically, a substantial non-difference and true unity that can be experienced in the most sacred part of each one of us, in the heart, abode of the Divine, is expressed to the other.

In all beings, there is a sort of conscious search for unity urged by the need to heal a deep and concealed sense of division. Therefore, the attempt is made to realize union and harmony, a primordial plenitude. Each human being seeks it differently: in the contact of the senses with their objects?; investigating the

nature of the senses and one’s mind, to rediscover one’s true Reality and, lastly, that there has never been any separation?

These queries were not unknown to the Hindu sages and seers, the rishi, who investigated the nature of the world, the human being and the Absolute and elaborating knowledge and methodologies intended to realize the scope of life. The concept of unity is evident in the term yoga present in the Veda. Panini mentions two Sanskrit roots: yujir, in the sense of “to unite”, “to join”, and yuj, expressing a state of deep meditational absorption.

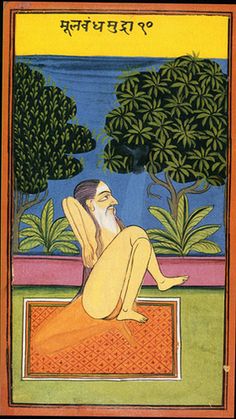

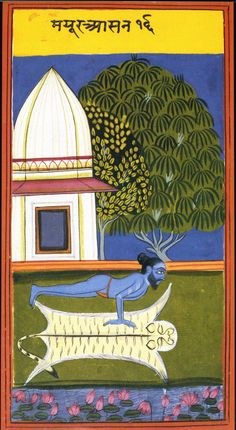

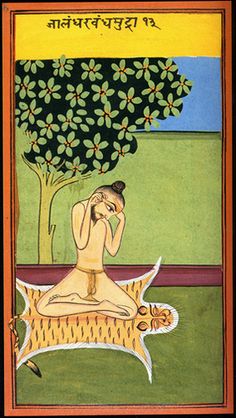

According to tradition, the Veda are considered eternal so the attempt to date them may be irrelevant. Similarly, it is difficult to date exactly the origin of Yoga as a practical philosophical system. We certainly cannot ignore the finding of some sandstone seals from the Indus Valley Civilization bearing representations of men and Gods in an evident yogic posture, padmasana and siddhasana. This attests the great antichity of Yoga.

It is interesting to note that Yoga does not only have spiritual or philosophical meanings but it can be used in various contexts with its general meaning “to unite”; for example, unite the cart to the horse, or in astrology, to indicate the conjunction of planets, constellations, in medicine, in geometry, in amatory arts and so on. Nevertheless, the term clearly acquires in the history of Indian religiousness esoteric connotations and a double value: method or discipline and state of being.

On the other hand, in some scriptures these two meanings are used together to indicate the union of the individual soul, atma, with the Absolute, paramatman. So here comes the issue of the various uses of the term Yoga according to the theological and philosophical setting of each school and tradition.

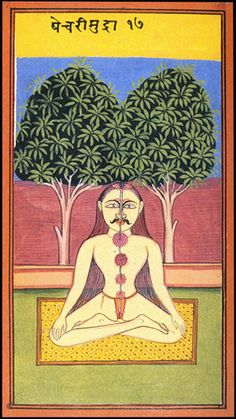

In the Maitrayani-upanishad, Yoga is described as “a state in which the senses, the mind and the prana are unified and silenced”. In his Yoga-sutra, Patanjali, rather than depicting Yoga as an immersion into the Absolute, highlights it as a state of separation in which the individual soul definitively deconditions itself from contact with matter, prakriti, and remains in a state of perfect isolation, kaivalya, but in a perfect union with the Absolute, as purusha.

In the Bhagavad-gita, Yoga is described as the state in which one separates from union with pain.

YOGA: A SOLUTION TO PAIN

Through the centuries, the human being has inevitably had to face the problem of pain that can have different aspects in different individuals, societies, eras, but remains a prerogative of nature, of life and manifestation. Even joy is always accompanied or followed by pain. If you own something, you’re afraid of loosing it; if you don’t have something you want, you suffer; often, the happiness of one means the unhappiness or deprivation of others. So, what seems nectar today, the Bhagavad-gita states, will be poison tomorrow. How can we free ourselves from this pain?

A solution comes from Yoga that investigates the nature of pain and “devises” a sure way to realize a radical emancipation from it. From this point of view, Yoga can be compared to a medicine that treats not only symptoms, but permanently eradicates the “existential malady” that afflicts the human being: ignorance (avidya).

The Yoga scriptures state that the root cause of pain is this ignorance that leads the human being to identification with the objects of the senses and leads him to think that they are the source of happiness. It is in this false perception that the human being repeats the experience of pleasure and so impresses in the subconscious the seed of a future experience and so on in the process of birth and death. The scope of life, therefore, is to break free from this storage of impressions and discover one’s own true divine Nature that is freedom and joy.

The role of Yoga is to remove this ignorance through the process of discrimination between what is real and what is not real, through the elimination of mental modifications. These are compared to the waves of a lake that ripple its surface covering the clearness of the water. The scriptures state that the human being is like water, pure and crystal clear, but assumes various colours when in contact with the senses and their objects. It is therefore obvious that Yoga cannot be considered a simple set of gymnastic or psychic practices, but rather a system of ethical and philosophical values combined with an unmatched scientific methodology that investigates every aspect of the human being: physical, emotional, vital, unconscious, intellectual, psychological, spiritual… Yoga is a means of consciousness; a journey from individuality to universality.

The role of Yoga is to remove this ignorance through the process of discrimination between what is real and what is not real, through the elimination of mental modifications. These are compared to the waves of a lake that ripple its surface covering the clearness of the water. The scriptures state that the human being is like water, pure and crystal clear, but assumes various colours when in contact with the senses and their objects. It is therefore obvious that Yoga cannot be considered a simple set of gymnastic or psychic practices, but rather a system of ethical and philosophical values combined with an unmatched scientific methodology that investigates every aspect of the human being: physical, emotional, vital, unconscious, intellectual, psychological, spiritual… Yoga is a means of consciousness; a journey from individuality to universality.

n the Bhagavad-gita, Yoga is equanimity and ability in action. Yoga teaches us to act with equanimity, unaffected by the opposites and not influenced by their fruits. Yoga leads to freedom, that is to say to full consciousness of oneself and of unconscious tendencies.

Patanjali states that Yoga favours the purification of the mind from the 5 great afflictions, klesha: ignorance, ego, attachment, aversion and attachment to life. For the realization of this, he gives a preparatory system divided in 8 stages, Ashtanga-yoga.

YOGA: VALUABLE AND ETHICAL HERITAGE FOR HUMANITY

The first assumption of the yogic discipline is a firm ethical basis. A code of conduct (yama and nyama) that governs the relationship one must have with others and with oneself. For this reason, Yoga is also a invaluable treasure for healing the disease of contemporary individualism which shows the “other” as a threat to one’s wealth, role, security and serenity. Yoga gives principles that extend to everyone, it does not make any distinction of class, gender, race or creed.

It offers a range of eternal and universal values, nourishing harmony among peoples. These include the principle of not harming, of not desiring more than is necessary, being satisfied with what one has, the principle of truth, of charity, and so on, to form an ideal fabric of peace and solidarity among beings.

Yoga teaches to see God in all beings and to be happy for the happy, compassionate towards the suffering, pleased with the virtuous and indifferent to the wicked. From this point of view, Yoga is an ancient and current resource, necessary more than ever.

DIFFERENT PATHS TOWARDS ONE GOAL

Yoga is generally subdivided in 3 great categories even if there are many more: karma, bhakti, jnana or raja.

Although the definitions of Yoga are different, all of them encourage to follow a constant discipline, abhyasa: to develop complete non-conditioning from the objects of the senses, vairagya; an undisturbed and calm mind, ekagrata. Such categories are paths leading to the same goal and cannot be divided one from the other. They are functional at the beginning to help the practitioner in choosing a suitable path; some are more prone to action, some are more emotional, some are more intellectual. At a certain point, these different paths flow into a conscious abandon to Ishvara (Ishvara pranidhana), up to the full realization of the identity with God, to freedom from the bonds of ignorance keeping an attitude of loving service to all beings.

KARMA YOGA

Through action (karma), the path of action with unattachment, without selfish ends.

JNANA YOGA

Through knowledge (jnana), the path of perfection through consciousness of Reality, that is not intellectual knowledge.

BHAKTI YOGA

Through love and devotion (bhakti), attitude of abandon to Divine will, this path leads to God through aspiration and emotional tendencies.

THE SCOPE OF YOGA: MOKSHA

Liberation from ignorance that prevents from experiencing infinite bliss. “I know that Supreme Being, glowing like the Sun that shines on the other shore, beyond obscurity.” (Shvetashvatara-upanishad, 3.8)

Moksha is a right of all animate and inanimate beings. The scriptures mention liberation for all (krama-mukti) in a long cycle of lives; the human being, however, can accelerate this process and, compared to animals, plants and minerals, consciously follow the path to liberation. According to the various philosophical traditions, liberation is variously explained; however, for all, he who consumes the motivations that lead him to rebirth (karman) is free from the cycle of (birth and death). This may happen when one leaves the body (videha-mukti) or when still in life (jivan-mukti); the latter is the case of Gurus and mystics who choose to take a body to help their disciples on their evolutionary path. The concept is similar to the Buddhist Bodhisattva.